Caschi Bianchi Georgia

L’eco degli eco-migranti | The unheard echo of eco-migrants

Scritto da Arianna Benesso, Casco Bianco con Apg23 in Georgia

Eco-migranti in Georgia, il IV Forum: “Rispondere alle sfide della migrazione ambientale: il reinsediamento come strategia a breve termine” organizzato da Europe Fundation a Tbilisi, raccontato da Arianna, Casco Bianco a Batumi.

“Quello degli eco-migranti è un problema che si è accumulato e ingigantito durante gli anni. I servizi dovrebbero essere garantiti a tutti equamente indipendentemente dalla posizione geografica. Sono sicuro che se Tbilisi fosse colpita da una catastrofe naturale, tutti quanti si prenderebbero la questione a cuore” è questa una delle provocazioni pungenti che Archil Khakhutaishvili, Direttore Esecutivo della ONG Institute of Democracy, ha lanciato ai rappresentanti del Governo georgiano durante il IV Forum: “Rispondere alle sfide della migrazione ambientale: il reinsediamento come strategia a breve termine” organizzato da Europe Fundation all’Holiday Inn Hotel a Tbilisi il 1 febbraio 2017. La nostra organizzazione Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII Georgia ha partecipato alla conferenza assieme a diversi rappresentanti della società civile georgiana. Il Forum è stato organizzato con l’obiettivo di dare suggerimenti ed esempi di pratiche virtuose ai rappresentanti del governo.

Per prima cosa è necessario capire che cosa si intende con il termine “eco-migrante”. Terremoti, valanghe e inondazioni sono alcune delle cause che possono costringere delle persone a lasciare la propria terra e a trasferirsi in un luogo più sicuro. Tecnicamente, si tratta di sfollati interni, ma la legge georgiana non riconosce loro questo status, per tale motivo è difficile quantificare quanti siano. Ciononostante, recenti dati del 2015 riportano che il numero degli eco-migranti in Georgia si aggirerebbe attorno alle 35.200 persone.

Per capire meglio la situazione, ci siamo rivolti a una serie di rappresentanti delle ONG georgiane e del Governo. CENN – Caucasus Environmental NGO Networks – ci ha informato che, nonostante l’assenza di un status legale, esistono due tipi di categorizzazione degli eco-migranti: la prima categoria comprende coloro la cui casa è talmente danneggiata da un evento naturale che non è più possibile abitarci, la seconda categoria invece riguarda quelle persone la cui casa non è danneggiata ma situata in un’area ad alto rischio di catastrofe naturale.

Secondo il decreto 779 del Ministero delle Persone Sfollate Interne dai Territoti Occupati, Reinsediamento e Rifugiati della Georgia, alle famiglie che rientrano nei sopracitati canoni di eco-migranti vengono offerti massimo 25000 lari, circa 9500 euro, per comprare un appartamento. È stato recentemente creato un data base elettronico che registra le richieste per accedere al progetto di ricollocazione delle famiglie, ogni richiesta riceve un punteggio che viene inserito in una graduatoria. Kote Razmadze, responsabile del Dipartimento per gli Eco-Migranti all’interno del Ministero degli Sfollati Interni dai Territori Occupati, Ricollocazione e Rifugiati della Georgia, durante il forum ha annunciato che le procedure di richiesta di un alloggio saranno semplificate in quanto “prossimamente sarà possibile fare domanda direttamente presso gli uffici pubblici locali e non solamente a Tbilisi”.

C’è un generale riconoscimento da parte della società civile georgiana dei progressi in materia di tutela degli ecomigranti. Secondo Khakhutaishvili (IoD) c’è stata un’evoluzione in positivo, “se dapprima le persone venivano ricollocate in altri villaggi senza poter scegliere, adesso grazie a questo decreto possono scegliere liberamente dove risiedere, solitamente scelgono di risiedere vicino a parenti e amici così da poter ricevere supporto”.

Ramaz Jincharadze, Viceministro della Salute e degli Affari Sociali nella repubblica Autonoma dell’Adjara ci ha informato che dallo scorso anno la Repubblica Autonoma dell’Adjara ha stanziato 3 milioni di lari all’anno per finanziare l’acquisto di case. In media sono state comprate 10 case all’anno da quando il programma è stato introdotto. Secondo il Vice Ministro, il programma continuerà finché tutti gli eco-migranti in Adjara non saranno reinsediati. Si è, inoltre, dimostrato fiducioso che per la fine di quest’anno tutti gli eco-migranti rientranti nella prima categoria in Adjara saranno trasferiti in una nuova casa: “Non sono a conoscenza del numero esatto di eco-migranti che appartengono alla prima categoria, ma ci sono circa 600 famiglie in Adjara che rientrano in almeno una delle due categorie”. Ha anche aggiunto che “se il numero di famiglie rimarrà invariato, la situazione sarà risolta nel giro di tre o quattro anni”. Gli eco-migranti non ricevono nessuna forma di aiuto sociale in termini di supporto psicologico né hanno accesso all’istruzione e nessuna attenzione speciale viene data alle persone con disabilità. Secondo Jincharadze “è importante in primo luogo dare a queste persone una sistemazione, solo dopo gli altri problemi possono essere presi in esame”. Per quanto riguarda le proteste degli eco-migranti in Adjara e nel resto del Paese, il Viceministro ha affermato: “Stiamo già facendo il massimo che possiamo fare”.

Tuttavia, la società civile georgiana non sembra essere così ottimisa come il politico adjaro. Durante il Forum, diverse ONG hanno sottolineato il fatto che gran parte dei problemi sta sia nella mancanza di un approccio olistico alla questione sia nelle complicazioni generate da una burocrazia miope. Ci sono stati casi dai risvolti kafkiani in cui famiglie non hanno potuto accedere a una dimora sicura, nonostante le proprie case non avessero né un tetto né un pavimento agibile, perché secondo la perizia tecnica, le abitazioni, avendo muri stabili, risultavano abitabili. Khakhutaishvili (IoD) ha anche sollevato la questione della migrazione di ritorno: in mancanza di integrazione sociale e occupazione nel contesto d’arrivo, un numero sempre crescente di famiglie decide di tornare alla residenza precedente, correndo il rischio di essere nuovamente vittime di una catastrofe naturale. Purtroppo, non c’è nessun tipo di monitoraggio dopo il reinsediamento: molto di frequente, le case comprate dal governo vengono rivendute dagli stessi beneficiari, perché questi non hanno altre fonti di reddito.

Se da un lato l’assenza di attività generatrici di reddito è un tema che lo stato non sta prendendo in considerazione, d’altra parte la società civile si sta facendo carico di questo problema. CENN qualche anno fa ha condotto un progetto pilota nel villaggio di Pirosmani nel Khakheti con l’obiettivo di generare opportunità di lavoro e favorire uno stile di vita sostenibile per 16 famiglie, tramite la realizzazione di giardini di albicocchi. A questo proposito, durante il progetto sono stati organizzati degli incontri formativi specifici di giardinaggio e di utilizzo del compost.

Al momento, l’associazione Young Scientists’ Union Intellect (Intellect) sta implementando un progetto biennale “Migliorare la situazione dei migranti nella regione dell’Adjara” che si concluderà a giugno 2017 con l’obiettivo di facilitare l’accesso al mercato del lavoro per questi eco-migranti. Il progetto ruota attorno a tre componenti: la prima riguarda training formativi per più di 20 diverse professioni; la seconda si basa sull’ accesso a micro-credito per iniziare attività commerciali o finanziare quelle già esistenti, come officine o panetterie; infine, la terza ha a che vedere con consulenze legali di carattere generale. Per accedere al progetto, i candidati devono presentare la documentazione che attesta il danno ecologico subìto dalla loro abitazione. Tra i beneficiari del progetto ci sono 25 famiglie che vivono in una baraccopoli a pochi chilometri da Batumi nella municipalità di Khelvache Uri.

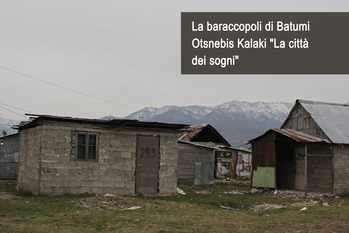

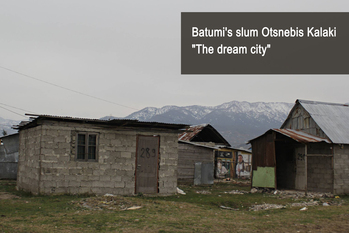

La baraccopoli si chiama “Otsnebis Kalaki”, ovvero “La città dei sogni”, ma di idilliaco non ha proprio nulla. Qui vivono circa 3000 persone in baracche di fortuna costruite con materiali di recupero e le condizioni igienico-sanitarie sono scarsissime data l’assenza di una rete fognaria e di strade asfaltate. Parte del progetto prevede anche l’installazione di alcuni container provvisti di docce e di lavatrici. Uno dei rappresentanti di Intellect ha affermato: “Stiamo facendo quello che il governo dovrebbe fare: alla fine del progetto ci aspettiamo che i nostri beneficiari abbiano acquisito più consapevolezza dei loro diritti.”

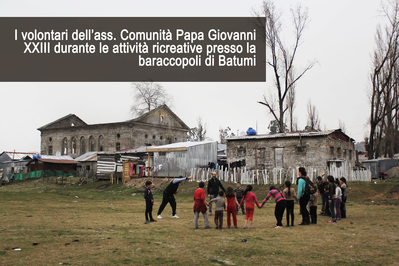

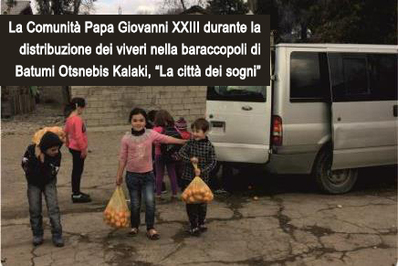

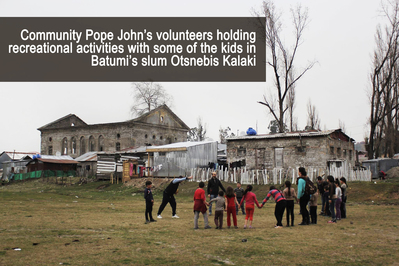

La Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII, che lavora da anni nella baraccopoli, conosce molto bene la situazione e regolarmente fornisce ad alcune famiglie selezionate cibo, medicine e pannolini. Inoltre, svolge attività di animazione e di insegnamento della lingua inglese.

Un’altra questione spinosa che riguarda la situazione degli eco-migranti è la mancanza di titoli di proprietà. Melud Vashahmadze, eco-migrante residente in una baracca a Otsnebis Kalaki, riporta in un’intervista ad una testata locale che il governo gli avrebbe assegnato una casa senza contratto e che quando il proprietario sarebbe tornato a reclamare la casa, lui sarebbe stato costretto a cercare riparo nella baraccopoli di Batumi. Tuttavia, durante la nostra intervista, il politico adjaro Jincharadze ci ha assicurato che questo è un problema del passato, “adesso, grazie al decreto 779, in pochi giorni le persone beneficiarie di una casa ricevono la relativa documentazione”.

Secondo alcune ONG come Intellect e CENN, uno dei maggiorni problemi è l’assenza di uno status legale per gli eco-migranti. Tuttavia, secondo Khakhutaishvili (IoD), lo status farebbe sorgere ulteriori problemi, poiché significherebbe stabilire non solo i requisiti di idoneità ma anche quando lo status dovrebbe decadere: “Dovrebbe decadere quando le famiglie ritornano al luogo d’origine o quando la loro situazione socio-economica è risolta? Invece di discutere sullo status legale, bisognerebbe dare alle municipalità locali più risorse finanziarie e mezzi per sviluppare competenze adeguate.” Tra le svariate raccomandazioni che IoD ha inviato al governo, ci sono quella di rafforzare la comunicazione tra il governo centrale e le municipalità locali passando da una forma di comunicazione verbale ad una per iscritto, e quella di fissare degli standard comuni per le persone vittime di disastri naturali.

A conti fatti, la questione degli eco-migranti sembra molto lontana dall’essere risolta. Sono molti i fattori che devono essere presi in considerazione, specialmente se si considera che circa 2000 famiglie in Georgia sono in condizioni di vulnerabilità o sotto rischio permanente di essere colpiti da una calamità naturale.

Il Forum a Tbilisi si è concluso con sorrisi e strette di mano come per ricordare a tutti i presenti che è necessaria una volontà politica congiunta coordinata con l’azione della società civile. Il nostro augurio è che dalle parole e dai convenevoli si passi ai fatti, cosicché la voce di coloro che hanno perso tutto non resti solo un’eco inascoltata.

Eco-migrants in Georgia, IV Forum “Responding to the challenges of environmental migration: resettlement as a short-term strategy” organized by Europe Foundation in Tbilisi, told by Arianna, White Helmet in Batumi

“Eco-migrants’ resettlement is a problem than has been accumulating throughout the years. Services should be provided equally regardless of the geographical position. I am sure that if a natural disaster occurred in Tbilisi everyone would be alerted”. This is how Archil Khakhutaishvili, Executive Director of Georgian NGO Institute of Democracy (IoD), provoked the representatives of the Government during the IV Forum “Responding to the challenges of environmental migration: resettlement as a short-term strategy” organised by Europe Fundation at the Holiday Inn hotel in Tbilisi on February 1st 2017. Our organisation, Community Pope John XXIII, also in Georgia, took part at this conference, along with several representatives of Georgian civil society. The Forum had the goal of providing the representatives of the government with suggestions and examples of good practices.

Firstly, it is important to address who and what are there “eco-migrants”. They are the people who have been forced to flee their homes and find new accommodation elsewhere because of earthquakes, avalanches, flooding and other natural disasters. Technically, they are internally displaced persons but Georgian law does not recognise them with this status. That is why it is difficult to quantify the number of eco-migrants. Nevertheless, recent data from 2015 state the number of eco-migrants is around 35200 people.

To better understand the situation of eco-migrants, we have gotten in touch with various representatives from Georgian NGOs and the Government. CENN, the Caucasus Environmental NGO Networks, informed us that in spite of the absence of a legal status defining eco-migrants, there are two types of categorisation: those who fit the first category, who have had their house fully or partly damaged and no longer suitable for habitation, and those families who fit the second category, who live in a house located in an area at high risk of being subject to natural hazards.

Under decree 779 of the Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accomodation and Refugees of Georgia, which came into force in 2014, those who fit the aforementioned categories are eligible for receiving a maximum of 25000 GEL (approximately 9500 EUR) to buy a house anywhere in Georgia. Recently, a database that registers all the applications for the programme has been created, each applicant receives a score which determines how to prioritise and distribute housing. According to Kote Razmadze, Head of Department of Eco-migrants Issues in the Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accomodation and Refugee of Georgia, “soon it will be also possible to apply for the programme directly at local public offices not only in Tbilisi”.

Khakhutaishvili (IoD) remarked that there has been a positive evolution in the treatment of eco-migrants, stating that “if before they could not even choose where to start a new life, but were relocated in other villages without being asked, now thanks to this decree they have the opportunity to choose where to live: usually they prefer to settle not far from their relatives and friends”.

Ramaz Jincharadze, Deputy Minister of Health and Social Affairs in the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, informed us that since last year, the Adjara Autonomous Republic has been allocating 3 million GEL per year to finance the purchase of a house. This has meant that an average of 10 houses have been bought per year since this programme was introduced. According to the Deputy Minister, the programme will go on until all Adjara’s eco-migrants have been relocated. He is also confident that by the end of this year all the eco-migrants fitting the first category in Adjara will have been relocated to a new house, stating “I do not know the number of eco-migrants of the first category, but there are approximately 600 families fitting at least one of the categories in Adjara”. He also added that “if the number of the families remains the same, the situation will be resolved in three to four years”. Eco-migrants do not receive any form of social help in terms of psychological support nor access to education and there is little to no attention given to the needs of persons with disabilities. According to Jincharadze “it is important to give these people a house first, before other problems can be taken into account.” In reference to the protests held by eco-migrants around Adjara and the rest of the country, the Deputy Minister affirmed: “We are already doing as much as we can”.

However, Georgian civil society does not seem to be as optimistic as the Adjarian politician. During the Forum, several NGOs pointed out that a lot of the problems lie with the lack of a holistic approach as well as myopic bureaucratic burden. There have been cases where families could not access a safe house, with Kafkaesque situations where houses did not have neither suitable flooring nor a roof, because, according to specialists’ evaluation, the house, having stable walls, was suitable for habitation. Khakhutaishvili (IoD) also raised the issue of back migration: in absence of social integration and employment upon arrival, an increasing number of families are deciding to go back to their previous residence, taking the risk of being victims of natural catastrophes again. Unfortunately, there is no monitoring after relocation: frequently, the houses bought by the government have been resold by the beneficiaries because they did not have a ready source of income.

The lack of income-generating activities is a problem that the state has not been taking into account. Civil society organisations have taken up the slack. Some years ago, CENN led a pilot project in Pirosmani in Khakheti, with the aim of generating employment opportunities and sustainable livelihoods for 16 families through the creation of apricot gardens. To this end, the beneficiaries were provided with special training on tree planting and waste composting.

Currently, the Young Scientists’ Union Intellect (Intellect) has been carrying out a two year project “Improving the situation of migrants in the Adjara region” that will end in June 2017 with the goal of easing the access into the labour market for these eco-migrants. The project is made up of three components: the first one involves training for more than 20 different professions; the second one is based on microcredit provisions to set up new businesses or to finance already existing commercial activities, such as motor garages and bakeries; finally, the third one introduces general legal consulting. To access the project, applicants must provide the documentation testifying that they fled their home because of ecological damage. Among the beneficiaries of the project are 25 families living in a slum located a few kilometres away from Batumi in the municipality of Khelvache Uri. The slum is called “Otsnebis Kalaki”, that is “The dream city”, but it is far from being a dreamy place. Here, approximately 3000 people live in makeshift shacks with poor sanitation and hygiene

conditions given to the absence of a sewer system and paved roads. Part of the project implies the presence of containers in the slums where the dwellers can wash themselves and their linen. One of the representatives of Intellect affirmed: “We are doing what the Government is supposed to do: at the end of the project we expect our beneficiaries to have acquired more awareness of their rights.”

Community Pope John XXIII is well aware of this situation and has been working in the slum for years, providing some of the families with food, napkins and English lessons.

Another thorny issue surrounding eco-migrants’s situation is the lack of property rights. Melud Vashahmadze, an eco-migrant living in a shack in Otsnebis Kalaki, claimed, during an interview to a local newspaper, that the Government had assigned him a house without providing him with the legal documentation. Sometime later when the owner of the house came to claim the house, Vashahmadze had to seek shelter in Batumi’s slum. During our interview, Adjarian politician Jincharadze informed us that this is a problem of the past, “now, thanks to decree 779, in a few days all the people who have been assigned a house should receive the relevant documentation”.

For some NGOs such as Intellect and CENN, one of the biggest problems is the lack of legal status for eco-migrants. However, according to Khakhutaishvili (IoD) establishing a status would give rise to further problems as it would mean having to establish who will be eligible for the status and when the status should expire. “Should it expire when they go back to their place of origin or when their socio-economic problems are solved? Instead of discussing on the legal status, we should provide our local municipalities with more financial resources and competences”.

Among the recommendations that IoD has given to the government, there is a call for strengthening the communication between the central government and the local municipalities by shifting from verbal communications to written communications, as well as by fixing common standards to deal with persons affected by natural disasters.

The issue of eco-migrants seems to be very far from being solved, there are many factors to be taken into account, especially considering that there are approximately 2000 families in Georgia who are vulnerable or under permanent risk of being victim of a natural disaster.

The Forum in Tbilisi ended with smiles, handshakes to remind everybody that there should be a joint political will coordinated with the work of civil society. Our wish is that words will be put into action so that the voice of those who lost everything will no longer remain an unheard echo.

Lascia un Commento

Vuoi partecipare alla discussione?Sentitevi liberi di contribuire!